Ha! If only it were that easy – run a quick google search, read a few blogs, tap a few keys and hey presto: one children’s book complete!

Sorry to disappoint but this isn’t actually a ‘how to’ post… it’s a ‘how did’ instead.

One of the questions I am most often asked by children when I visit schools and nurseries is “how long did it take you to write that?” and when I ask them to hazard a guess, answers range from a few minutes to a few years.

Some books have been easier than others to write and I think that a lot depends on the idea, the age range you are writing for and how naturally the plot develops. Ruan the Little Red Squirrel took a fair amount of planning because of the plot – that the campers move around the country and encounter different animals meant that I did a fair bit of research into what lived where, their habitats and so on so that the book had a good geographical reach and – for my publisher’s sake – made good commercial sense.

The Kilted Coo was more of an organic creation because it evolved from a rhyme inside my head. The idea actually came to me when I was working on Ruan because one of the animals I thought he might find would be a Highland Cow. The initial draft of The Kilted Coo was very quick to write, as the words and rhythm almost fell out of my mouth the way that children’s rhymes often do.

The latest – The Unicorn in the Castle – was a longer process. The book itself is longer; still the standard 32 page format for picture books but with a substantial amount of text aimed at a slightly more confident reader. The older children are, the more their books need to make sense and create atmosphere to engage them, and that takes time.

For those of you who are interested, here’s what actually goes into the production of a children’s book. It’s not, at least in my experience, a case of merrily handing over your manuscript and awaiting finished copies, fame and fortune.

What really does take time is editing and perfecting the draft. As a small-timer, I do my editing myself. This is sometimes an arduous process as there’s a fine line between thinking, “yes, I am so clever” and “oh, I am so boring”. Being critical and objective of your own ideas, but not overly so (as I have propensity to be), can be hard. Of course, before you submit your manuscript, you’re usually fairly confident in your work but there is always a lingering sense of your words being unfinished. I suppose it’s akin to whether or not an artist ever finishes a painting or, if given time, he would continually add small details to the canvas.

Repetition is often something that needs to be refined; I like having particular phrases that repeat in a story as it helps younger children to follow the story and gives them something to participate in when the story is read aloud. In Ruan, ‘there are no trees’ is repeated so often I’m sure it irritates parents but I have seen first hand that children respond to being able to anticipate part of the story. And of course it hammers home the message about where red squirrels live and the need to protect their environment.

That said, the overuse of common words is not effective repetition – really, very, good, said and did are all too often left ringing in a reader’s ears and I know from my teaching friends that kids are actively discouraged from using these words to improve their vocabulary. Finding alternatives that are age appropriate is occasionally a challenge, but children can be surprising in the words they know and understand. When in doubt, I usually look to other books aimed at the same age to garner which words might work.

Language aside, the word count can also be tricky for a picture book. Standard format dictates that the author has 32 pages in which to create and explore their world – while retaining space for all of the important information, title page and illustrations. I have (you may have noticed) a tendency to be a wordy person and in writing these books for children I have certainly honed my cutting skills; I thought cutting down academic work b a few hundred words was difficult – try rephrasing a short sentence in half the number of words, while still retaining flow, pace, mood and interest…

Speaking of flow, naturally the story should make sense and it should build – either to a climax, conclusion or a resolution. More practically than that though, the story has to flow physically across the 32 (or more often 30) pages at stake. Adults are adept at turning and page and retaining what was on the one prior. Children, however, are less so and I always write my books as though I was reading them aloud. I find that this clarifies where sensible pauses, changes in direction and developments should fall.

The other consideration of pagination is the illustrations. As an author, it’s important to be mindful of just what is and is not possible to illustrate in one page. With the best will in the world, even the most talented artist will not be able to cram in all of your varied and fantastical ideas to one double spread. The focus of the image needs to be the primary action of the story – at least in a text-led book (by which I mean one driven by the author, rather than a series of illustrations around which a story is told).

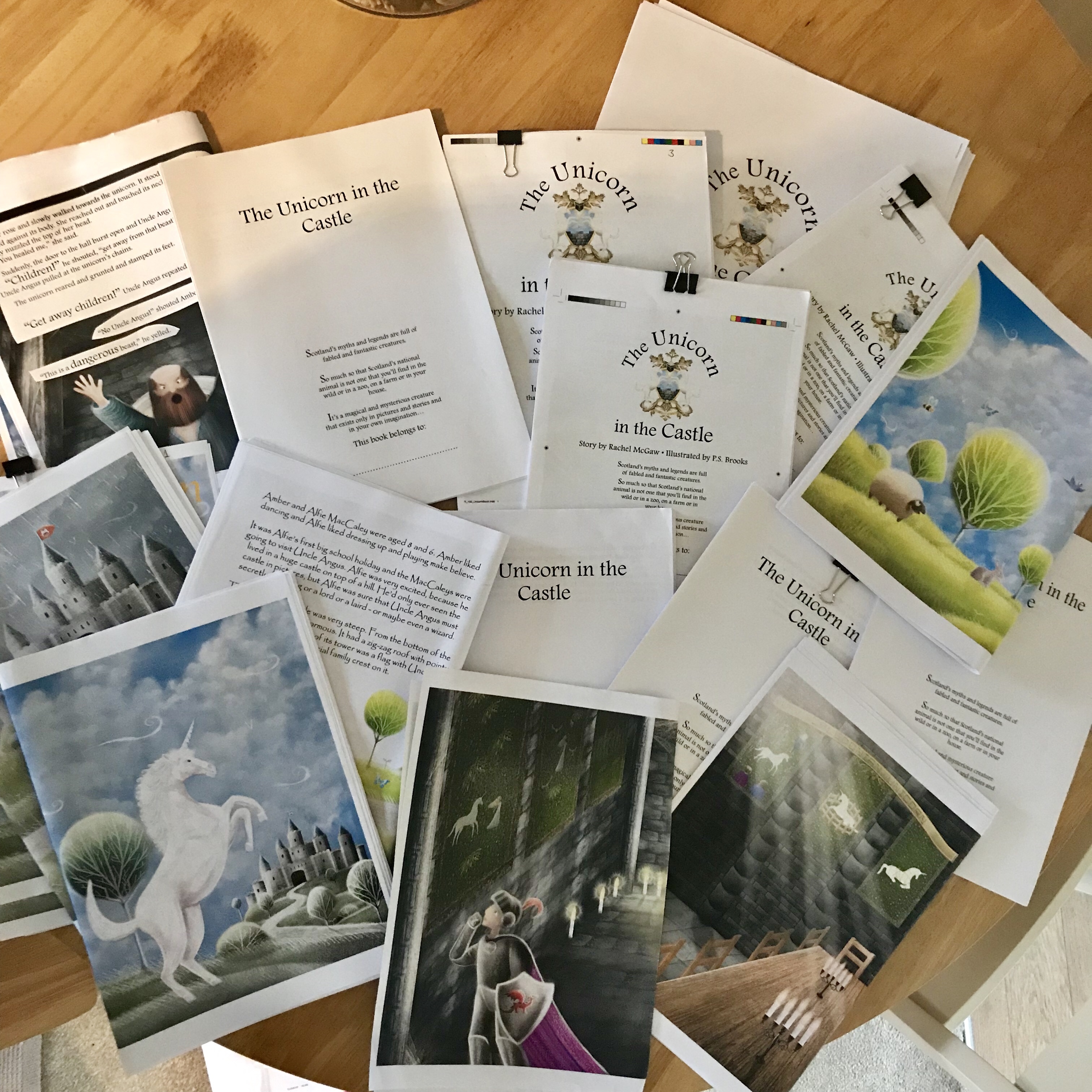

After the near-penultimate tweaks have been made to the manuscript, the next stage of the process I have experienced so far is to effectively storyboard the book for its illustrator. This is exactly as it sounds – take 32 pieces of paper and chop out the text. Then, the lucky illustrator is subject to my rudimentary sketches for how I envisage each page will look.

I have worked with a mixture of single pages and with double spreads. My preference is for double spreads as I think these are easier for children to focus on in their entirety. Double spreads also offer the opportunity for some more detail and intricacy in the images. Sometimes though, the story lends itself to some single page illustrations and as long as these are sparing throughout I don’t think they are too disruptive.

Working with illustrators is, I’m sure, a process that differs from publisher to publisher, author to author and illustrator to illustrator. I have been lucky so far to have quite a degree of creative control and have been able to work very closely with both my publisher and illustrators on how the final product looks. This inevitable results in several drafts of characters, spreads, layout, features, colours, seasons, scenes – all sorts.

As an indication of the dedication and hard work illustrators put in, I think the final illustrated draft of The Unicorn in the Castle was somewhere around Version 15.

Once the images have been finalised, the next stage of the process is to lay the text over the top. Again, I’ve been lucky to work with the artworker on this for The Unicorn in the Castle. Ahead of our collaboration, I was back with my scissors and 32 pieces of paper – this time illustrated – and I literally cut and pasted the text onto the sheets. Over the course of a few hours, working from the cut and stick job, we sat together and considered each sentence to decide where it would appear on the page, where each line breaks, the justification to the left, right or otherwise, the text colour, it’s shadow, it’s size, it’s impact on the illustration underneath… essentially every aspect of how the text looks. The more I work on books, the more I understand the intricacies involved in so many aspects that the reader takes for granted or, perhaps, simply doesn’t notice because of their effectiveness.

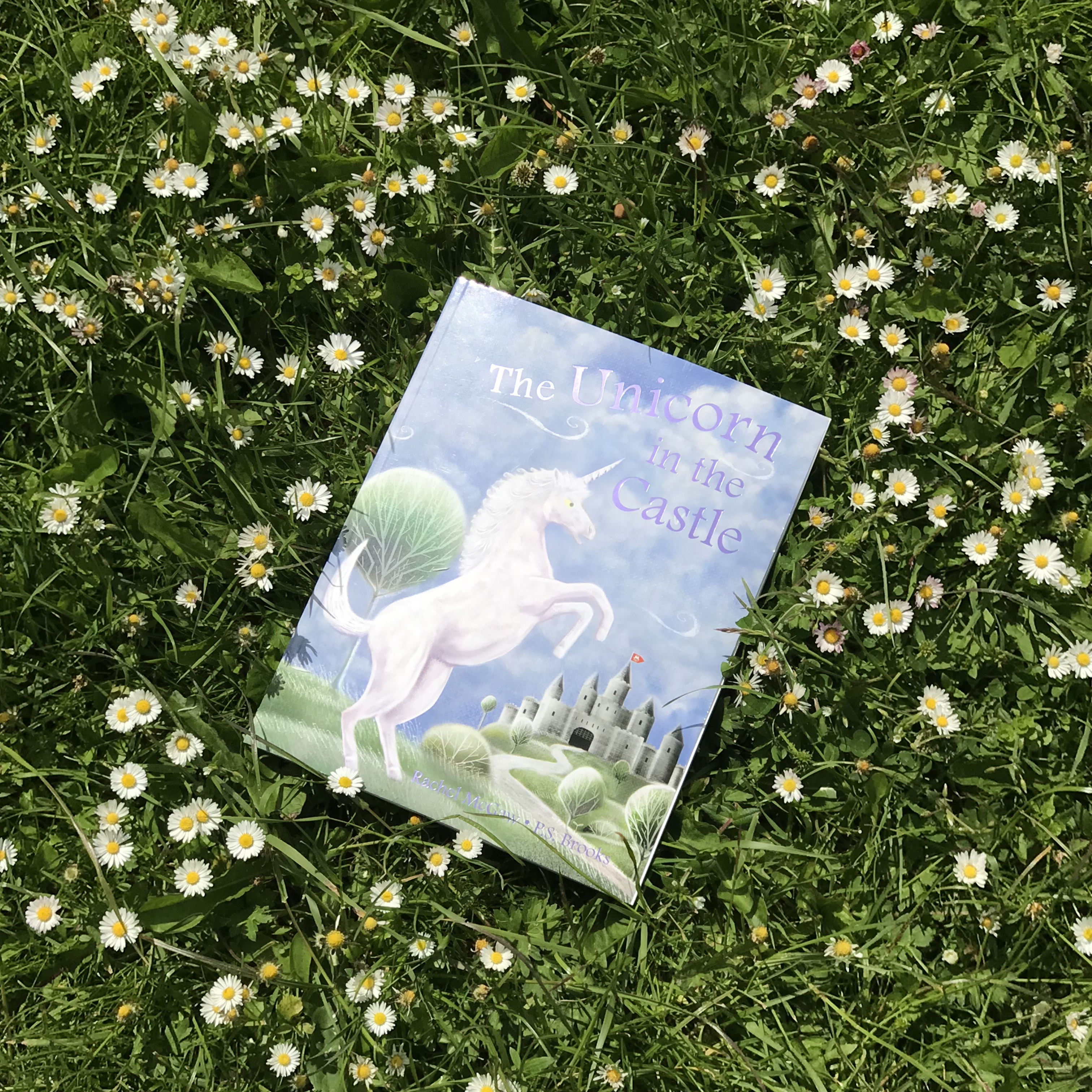

Once the inside is done, one of the most crucial decisions is the cover. Everyone judges a book by its cover – both those who pick the book up from the shelf and those who decide that it’s on that shelf in the first place. It’s so important to get the cover right. It has to be revealing enough about the story without giving everything away, enticing and intriguing without being confusing or misleading. The skill of the jacket design is in the illustrator and those who have the final say on the end result. It’s something that probably no one is ever 100% certain of, and something which can probably always be improved – just like the artist’s canvas.

There are practical decisions to be made by the publisher at this stage: the weight of the paper, the weight of the cover, any lamination, foiling, the price point. As author I have always written the blurb for the back but sometimes this is up to the publisher or those in marketing positions.

And then, after all of that work, the files are beamed through cyberspace to the printer. That’s usually the last I see of them until an advance sample arrives with my publisher, which is when it starts to feel properly real. By this point it’s really too late to make any changes so I always have everything crossed that the book is in order, as expected, and that all parties involved are happy with it.

I’m pleased to say, so far so good.

This is exactly the stage I have reached with The Unicorn in the Castle. My advance has arrived, the pages are thankfully in the right order, the colours look good, the cover is strong and the foil effect on the front (the colour of which was the subject of very protracted discussions) is bright and appealing. All that’s left now is to try to raise awareness of the book before publication – hence this blog and the others.

I really hope that this new book is well received as it’s been a long time coming and several people, myself included, have put in a lot of hard work.

The journey certainly doesn’t stop here for The Unicorn and in many ways a new stage of hard work begins. But meantime, here’s to the next one – already a work in progress…

Rachel

Wow! I loved reading this fascinating post about the creative process of writing a children’s book. It’s a really intriguing “behind the scenes” account of the complexities of taking your initial ideas and developing them into what becomes a beautifully completed piece of children’s literature. I love the personalised, humorous and incredibly informative content. It gives a real insight into your dedication, creativity and hard work to deliver such well conceived and captivating books for children.

I know from first hand in primary schools how readily young children engaged with Ruan and The Kilted Coo as we and other schools, used both books for literacy based topic work and children loved researching Scotland’s landscapes and native animals along the way ! Your author visits were a huge success and inspired many young writers to “have a go,”.

This article is a great read for pupils and adults who’ve ever wondered what it takes to become a published author and may well inspire them to “have a go!” too. Thank you Rachel!

LikeLike